THE MISSION DISTRICT

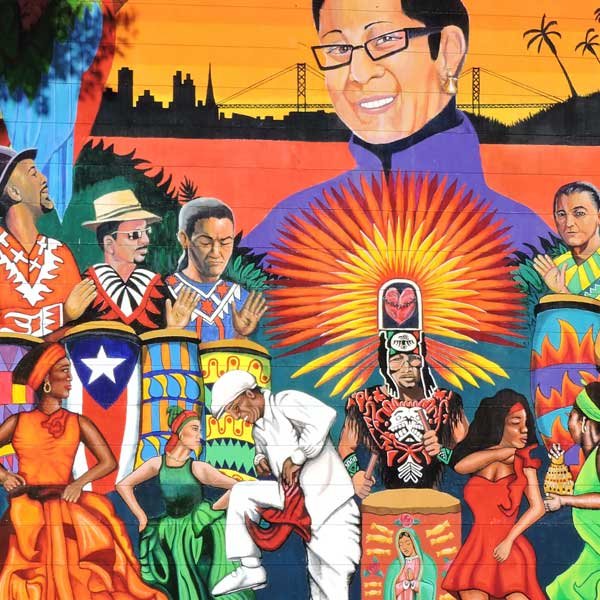

MURALS

It is said the Mission District has the greatest concentration of street art in the world. It is, in fact, hard to walk more than a block or two without beholding one of hundreds of murals that decorate walls, fences, doors and gates in the neighborhood. They are inspired by noted artists such as Diego Rivera, whose magnificent WPA-era works can still be found in the City, and encouraged by the resurgence of murals as a means of ideological and cultural expression in Mexico in the 1960s and ‘70s. The Mission’s iconic murals illustrate the hopes, dreams, hurts and fears of the diverse peoples who have made the neighborhood home.

Balmy Alley is parallel to Treat Avenue and Harrison Street, between 24th and 25th Streets, and features a treasure trove of mural art of a myriad of styles and subjects from human rights to local gentrification and Hurricane Katrina.

Clarion Alley runs parallel to 17th Street, between Valencia and Mission Streets. Many of the murals are the work of the Clarion Alley Mural Project, an artist collective founded in the early 1990s.

Precita Eyes Muralists is one of three U.S. community mural centers sponsoring ongoing mural projects. It offers maps, merchandise and tours of the districts murals, and provides technical support and mural supplies.

Lilac Alley runs parallel to Mission and Capp Streets, between 24th and 26th Streets, and features dozens of examples of contemporary street art.

The Women’s Building Maestrapeace Mural covers two sides of the first woman-owned and operated community center in the US, located on the corner of 18th and Lapidge Streets. This remarkable and inspiring mural celebrates the courageous accomplishments of women across the years from around the world. Not to be missed..

ART OF THE DEAD

José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913) was a Mexican lithographer and engraver whose images of folk heroes, sensational crimes and disasters were created to illustrate current news stories but, more often than not, stood on their own in such a way that they required no words at all. Evidence of his legacy may be seen on six of seven continents and is influential to generations of today’s artists, providing inspiration to fuel the imagery of today’s movements like Occupy, immigration reform and human rights. To those people who do know his work, his story is shrouded in myth. He is called a revolutionary, artist of the people, the Goya of Mexico and yet to most of the public he is virtually unknown.

However, if one looks with only a slightly educated eye, a rich legacy in Posada’s work may be seen. He lampooned politicians by creating wildly expressive images for his era's equivalent of the tabloid press. He graphically chronicled the Mexican Revolution and, forty years after his death, helped the Cuban Revolution succeed. His art, which commented on Mexican culture of his time, also adorned the concert tickets of the Grateful Dead. Today his art literally leaps to life each year as the skeletal figures seen each November during the Mexican observance of Day of the Dead. It is for those skeletal images (called calaveras in Spanish) that Posada is most well known.

The Mission District is filled with images drawn from Posada’s influence including the calaveras on the metal grates on Valencia Street, the calaveras in many of the murals scattered throughout the Mission and many of his images on products carried in Mission district stores, as well as the cover of Mission Guide. posada-art-foundation.com

A documentary about Posada entitled Searching for Posada: ART and Revolutions was recently completed. It tells the story of Posada and Mexican publisher Antonio Vanegas Arroyo and how their twenty-three year collaboration inspired and significantly influenced the graphic images of social movements from battling fascism, to protesting wars and crusading for civil rights. artandrevolutions.com

LOWRIDERS

In the mid '70s lowriders began to glide along the streets of the Mission barrio. Brightly painted, sleek looking cars, modified by young Latinos and Latinas, ride low on the ground. What you don't see is that they've been fitted with special hydraulics - pumps, dumps and cylinders - to make them bounce up and down to the rhythms of cumbia, salsa, oldies and Latin rock sounds.

The hobby gave birth to lowrider car clubs and the San Francisco Lowrider Council, creating a mass of machines with lowered chassis on hydraulic suspension. Other unique features include custom rims (often with spinners), narrow tires, engravings on the windows and chrome bumpers, multi-layer lacquered paint jobs, lush custom interiors with accessories like chain steering wheels and crushed velvet, and streamlined exteriors decorated with murals.

Lowriding in the Mission is a Latino/Chicano art expression that is not only cool, but a family affair. Aficionados often invest years of work and thousands of dollars in their creations. So as you travel the neighborhood streets, let your hand bow up and down at a lowrider in the Mission and watch the driver hit the switches to make the car dance up and down or side to side just for you. Show your appreciation by yelling, "Oralé!"

Check out the San Francisco LowRider Council's Facebook page for the latest Low Rider news and events.

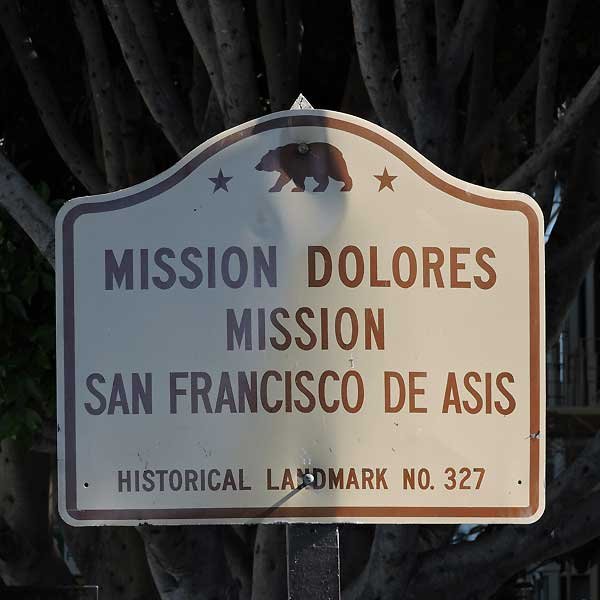

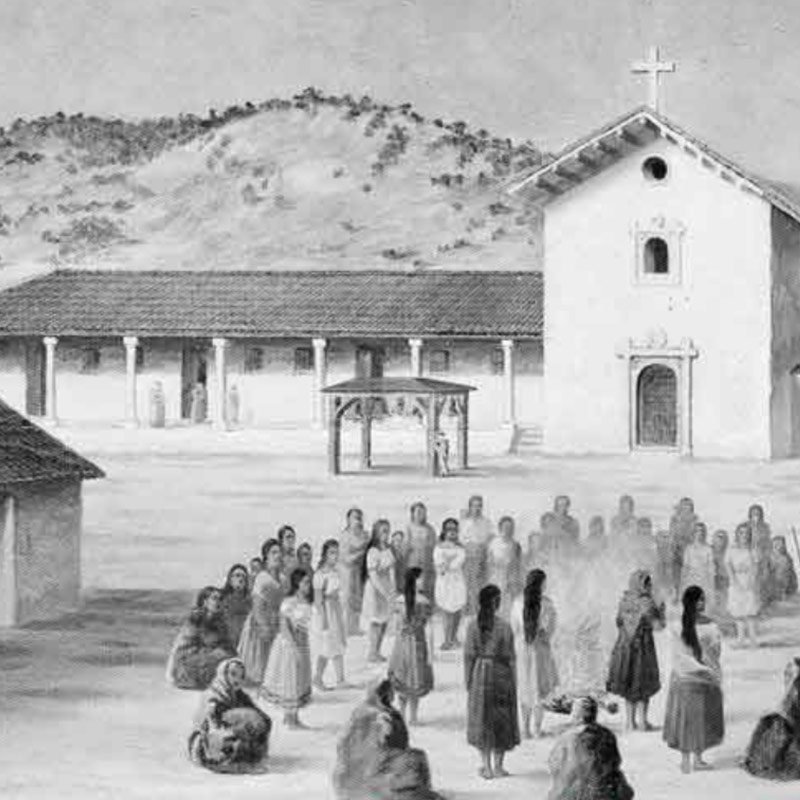

THE MISSION HISTORY

Today’s Mission District was originally the home of the Yelamu Ohlone Indians, who had two long-established villages here prior to the arrival of the first European settlers in the late 18th century. One of the first buildings erected by the Spanish missionaries in the 1780s remains the oldest standing building in San Francisco, the chapel at the neighborhood’s namesake, Misión San Francisco de Asís, better known as MISSION DOLORES. (3321 16th Street).

In the early to mid-19th century the area was home to ranchos of Spanish-Mexican colonists whose names still echo through the district: Bernal, Dolores, Guerrero, Valenciano, and others.

A crude two-mile road led northeast to the town of Yerba Buena (later renamed San Francisco). With the arrival of the Gold Rush and California statehood came a building boom, with substantial development of the Mission into housing for working class immigrants from Italy, Germany and Ireland, as well as factories in which many of these new residents worked.

In the post World War II era there was a large influx of Mexican immigrants, due in part to displacement by redevelopment in other parts of the City.

This was the beginning of the imprint of Latino Culture that continues to define the Mission today. That cultural influence was both deepened and broadened by the arrival of primarily Central but also South American refugee immigrants from the 1960s through the 1980s.

The decades on either side of the turn of this century marked a boom-bust-boom cycle that initiated continual rediscovery and re-investment in the Mission, but never so much so that the neighborhood lost its unique multi-cultural sabor.

READ MORE about The Mission's rich and vivid history.